Playing with Fire: The Interest Coverage of US Federal Government Revenues

Net interest payments are projected to eat over 20% of federal revenues in 2025, unprecedented for the US in modern history. The future could be much worse.

The federal government is playing with fire with its debt and deficits. Yes, the US dollar is still the world’s reserve currency, and Treasury bonds are still viewed as a safe haven. But no country is immune from bond markets becoming concerned enough about fiscal sustainability that they begin to demand compensation for the risk.

The danger is not so much that the US will outright default - although there is a market to bet on that and it has a positive price - but rather that the country would repay in very devalued dollars due to inflation. If interest payments on nominal dollar debt eat up a huge share of revenues, the pressure to let inflation drift up will be enormous. Inflation increases the number of dollars the US government takes in, even as it reduces the dollar’s purchasing power for consumers.

Lenders worried that profligate countries are going to let that happen typically extract punishment in advance by demanding much higher yield premiums for expected inflation and inflation risk. The result is much higher interest rates, sooner rather than later, which can create a fiscal crisis that pinches not only the government’s ability to provide services but also consumers and businesses.

A favored measure and focus of many studies of fiscal sustainability is the debt-to-GDP ratio. While this ratio has flashed warning signs, it’s only part of the story. According to OECD data for 2021, the last year for which fully harmonized data are available, the US’s debt-to-GDP ratio reached 125%. That’s a record for the US, higher even than when the country borrowed significantly to finance World War II. Yet other countries have larger debt-to-GDP ratios. Japan’s was top among the OECD at 244%, and nevertheless Japan has not faced a true sovereign debt crisis. Greece, which faced a major fiscal crisis last decade but today is trundling along came in at 225%, followed by Italy at 172%, and Portugal and the UK at 143%.

A debt-to-GDP ratio of 125% means that it would take 15 months of every dollar of value of goods and services produced in this US to pay off the national debt. But as these examples suggest, debt-to-GDP is not the best indicator of what investors actually care about. The real concern of creditors is rather whether the country will be able to roll over maturing debt, and whether creditors will will receive their promised payments on time and in currency that is still worth something.

What matters much more for those questions than the level of debt is cash flow relative to interest payments. That is why if you speak to investors in corporate bonds, they’ll tell you that probably the most crucial statistic for them to know about is interest coverage: can a company cover its interest payments with its cash flows? If not, the company is likely to default.

What is a “crisis” ratio of interest payments to government revenues? This of course depends on whether markets believe the government has both the scope and political will to address its fiscal imbalances. One of the more recent sovereign debt crises occurred when Greece had to “restructure” its debt in early 2012. Restructuring is a nice word but it means that some creditors did not receive payments that they were promised at the time they were supposed to receive them. That’s a default.

In 2009, 2010, and 2011 respectively, Greek government interest payments as a share of revenues were 13.4%, 14.7%, and 16.8% respectively, based on a 2012 IMF report.1 If one removes “Social Contributions” linked to government programs from the revenue measure, the ratio peaked at 24.1% in 2011. Of course, since Greece had adopted the euro it didn’t control its own money supply, so investors might reasonably have worried about an actual hard default as opposed to a slower monetization of debt.

Where is the US federal government’s interest coverage today? Using Table 1-1 from the latest (June 2024) updates to the Budget and Economic Outlook from the Congressional Budget Office (CBO), interest expenditures as a share of federal revenues will be 18.2% this year ($892 billion of interest on $4.890 trillion of revenue) and 20.2% in 2025 ($1.016 trillion of interest on $5.038 trillion of revenue), in the absence of changes to taxes or spending.

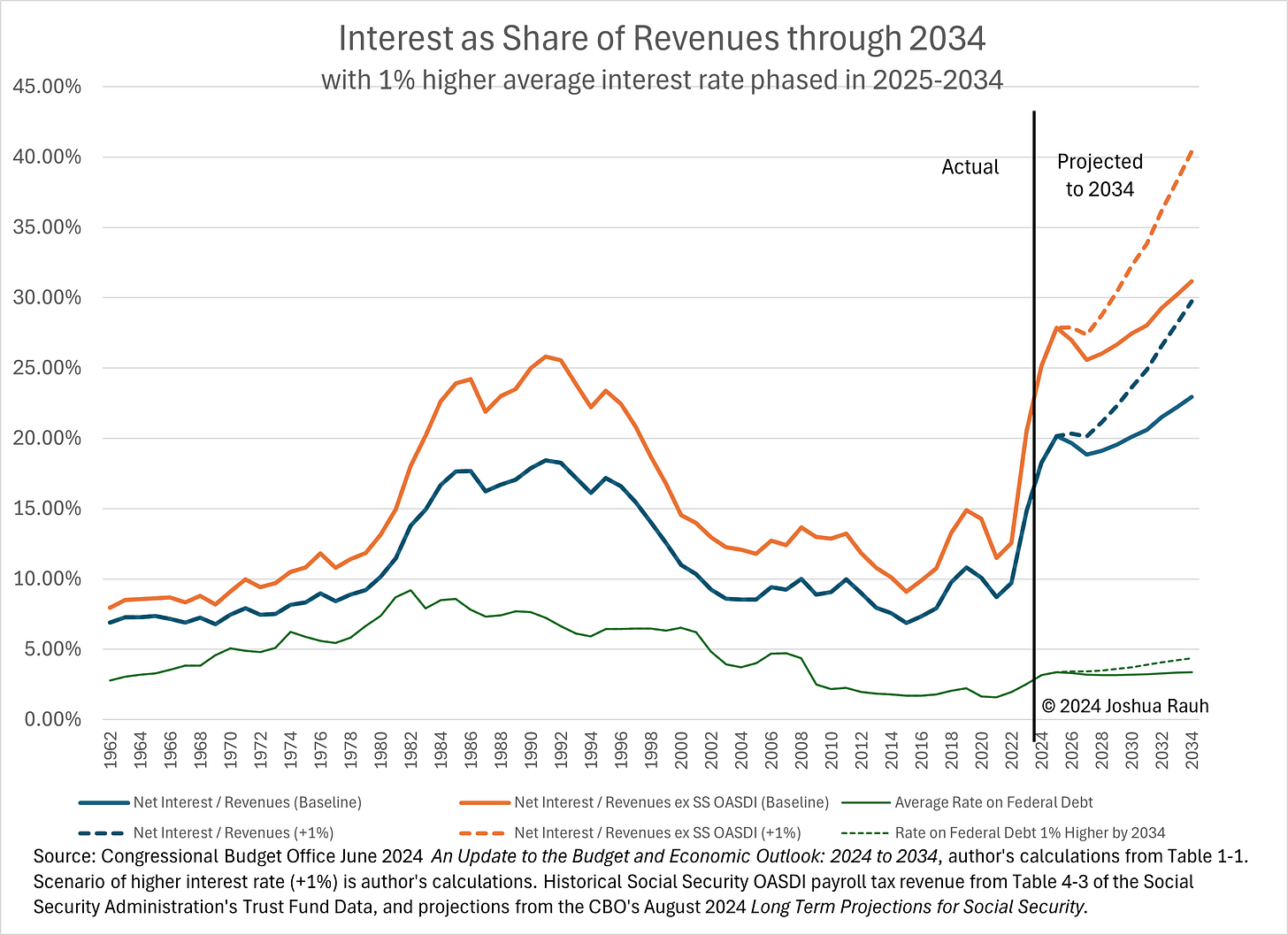

History shows that while the 18% threshold was crossed in the 1991, as shown in the graph below, we are in uncharted territory crossing the 20% mark. The graph also shows the average interest rate paid on federal debt, and the debt-to-GDP ratio (on the right axis).

In 1991, debt-to-GDP was only 44% but the government was paying an average interest rate of 7.23% per year on its debt. This rate was lower than in 1982 when the average interest rate reached 9.20%. At that time, the Federal Reserve under Paul Volcker was raising interest rates dramatically to bring down inflation, but the cumulative years of high interest rates and the increase in borrowing in the 1980s brought the interest-to-revenue ratio to its high of 18.4% in 1991.

I have also done a coverage calculation that uses the CBO’s figures and projections but removes in the revenue denominator the tax revenues from the Social Security Old Age and Disability Insurance (OASDI) program. This calculation is relevant under the assumption that these Social Security revenues, which already are insufficient to pay for those programs, are not accessible to pay interest. Under that scaling, the 2024 and 2025 interest-to-revenue ratios rise to 25.1% and 27.9% respectively, relative to the 1991 level of 25.8%.2

If we were just reaching 1991 levels of interest coverage but thought interest payments as a share of the budget would recede is it did later in the 1990s, there would not be cause for alarm. The problem is where we are heading.

The CBO’s regular updates include projections on a 10-year horizon. As the next graph shows, if I use CBO projections to calculate the interest-to-revenue ratio, it reaches 22.9% by 2034. Excluding Social Security and OASDI payroll taxes, using the CBO’s own projection of such taxes for the projection period, by my calculation interest payments would reach 31.1% of the remaining revenues.

But of course the CBO’s projections of interest payments depend on the CBO’s projections of interest rates, and projecting interest rates on a horizon of a decade (or decades) introduces much uncertainty. As the end portion of the green dashed line in the graph shows, the CBO expects the average interest rate on the federal debt to hardly budge over the next 10 years, sitting at 3.36% and 3.38% respectively in 2025 and 2034.3

Is this assumption reasonable? The CBO rate forecast is based on the maturity structure of federal debt combined with the CBO’s projections of market interest rates in the 2027-2034 period. Specifically, the CBO projects Fed Funds and 3-month Treasury Bill rates will settle at around 3% and the 10-year Treasury note will average 3.6% in 2027-2028 and 4.0% in 2029-2034. The average rate on federal debt of course changes more slowly than market interest rates, as the government only receives the new rates on new or maturing debt that it rolls over.

The CBO has an extensive economic modeling machinery that it uses to develop such forecasts. What emerges over this 10-year horizon is an economy settling in to roughly 2% real GDP growth or slightly lower, and 2% inflation. These forecasts are also broadly consistent with the Federal Reserve Board members’ own economic projections, and not far from market consensus forecasts.

Yet given the historical volatility of interest rates and the challenges with economic forecasting, there are considerable risks to the forecast. Central bankers around the world failed to predict the surge in inflation that occurred in 2022, and with that came much higher interest rates than the CBO, Federal Reserve, or most market participants were forecasting or expecting. And of course in the mid-1960s, markets were not expecting short-term interest rates to move up to 15% in 1980 as the Fed fought inflation.

But let’s not ask what would happen to interest coverage if the average interest rate on the federal debt were to reach its 1982 level of 9.2%, or even its 1991 level of 7.2%. Instead, let’s just consider what would happen if over the coming decade interest rates were slightly higher each year, cumulating in a 1.0% rate difference in 2034. That is, instead of ending the next 10 years exactly where we’re starting, at less than 3.4% as the CBO forecasts, what if the average interest rate the federal government paid on its debt crept up to just 4.4%? I perform this calculaiton in a simple way, by simply applying an adjusted rate path to the CBO’s projected debt balance.

The next graph shows that if this happens under current law, interest payments will consume 29.7% of revenues and 40.4% of revenues excluding Social Security OASDI payroll tax revenues. If you think there’s going to be appetite for accessing the Social Security payroll tax revenues for non-Social Security purposes, keep in mind that starting in 2035 the revenues from those taxes will only be able to fund 83% of the benefits.

The final scenario I will present extends the horizon to 30 years, through to 2054, using a combination of the CBO’s most recently published 10-year update from June 2024 and its long-term budget projections that it posted in February 2024.4 I present estimates of the interest coverage ratio under (i) the CBO’s baseline interest rate scenario, where the rate on federal debt reaches 3.8% in 2054 and (ii) a scenario where over the coming three decades, interest rates on federal debt are slightly higher each year, cumulating in a 3.0% rate difference in 2054. Under this latter scenario, the average rate on federal debt reaches 6.8% in 2054, still below the 7.2% level of 1991, and below any level of average rates seen in the 1980s.

Even under the CBO’s baseline interest rate scenario, interest payments consume 34.8% of revenues in 2054, and 45.7% of revenues excluding Social Security payroll taxes. Under the scenario of further rising rates, which I would still describe as moderate in comparison to the episode of the 1970s, interest payments rise to 62.3% of revenues and 81.9% of revenues excluding the Social Security payroll taxes. Here is a summary:

Interest-to-Revenue Ratios

Year Rates I/Rev I/Rev*

2024 Baseline 18.2% 25.1%

2025 Baseline 20.2% 27.9%

2034 Baseline 22.9% 31.1%

2034 Plus 1% 29.7% 40.4%

2054 Baseline 34.8% 45.7%

2054 Plus 3% 62.3% 81.9%

Rev* excludes SS OASDI

payroll tax revenuesThese scenarios are dire, and unfortunately they are not unlikely. If buyers of US debt see that the US is not interested in addressing its deficit, they will impose higher rates on us. An additional bout of inflation that might come from any of a number of sources — including a strong reverse in the globalization that has largely been deflationary for the US economy — and require further, even modest rate increases would also cause ever larger shares of the budget to be consumed by interest payments. Alternatively, perhaps the US government will decide to pressure the Fed to tolerate higher inflation, and use tools of financial repression that will keep the returns that can be earned by savers below the inflation rate.

Such events will take a massive toll on the US economy. They will also limit the US’s ability to invest in its military should it need to do so without incurring further inflation.

This could all be avoided by proactive measures to balance the budget and reform entitlements, but the political will to do so is obviously scarce. We may find we are paying the price sooner than we thought.

Calculation based on figures in the table “Greece: Revenues and expenditures relative to the EU average” in the IMF report Greece: Request for Extended Arrangement (2012). Interest coverage calculated as interest row divided by revenue row.

Specifically, the Social Security OASDI program is estimated by the CBO to generate payroll tax revenues of 12.87% and 12.97% of taxable payroll respectively for years 2024 and 2025, where taxable payroll is projected at $10.401 trillion and $10.774 trillion respectively for 2024 and 2025, yielding tax revenues of $1.339 trillion and $1.394 trillion respectively for those years. These projections are from the CBO’s August 2024 report on Long Term Projections for Social Security. Historical data on OASDI payroll tax income is from Table 4-3 of the Social Security Administration’s Trust Fund Data.

This calculation of the average interest rate on the federal debt comes from Table 1-1 of the CBO’s June 2024 Updates to the Budget and Economic Outlook: 2024-2034 as “Net Interest” divided by “Debt Held by the Public.” When conductd on the February 2024 release, Budget and Economic Outlook: 2024-2034, this process matches the average interest rates on federal debt reported by the CBO in its March 2024 Long Term Budget Outlook document. Hence, this is simply an update of that calculation.

This requirees some pasting and application of the long-term GDP growth rates implied in the February 2024 report, as well as an approach to handling the updated debt-to-GDP ratio - as of February the Debt/GDP ratio in 2034 was projected only to be 116% but by June that had been increased to 122%. I assume that the Debt/GDP ratio starts at that 122% level in 2034 and continues to grow by the same number of percentage points each year from 2034-2054 as it does in the February forecast, applying then the rate forecast to derive net interest.