There is a lingering global perception that the United States (U.S.) stands apart from other democratic countries in its approach toward economic governance. Many assume that the U.S. remains a bastion of free market capitalism that ruthlessly prioritizes efficiency and innovation over any commitment toward equality of outcomes. Many have even gone further, suggesting that the entire economic tax system is “rigged” in favor of wealthy taxpayers. In one Pew Research poll from 2020, for example, 86 percent of Americans said that there was too much inequality in the country and that the government should raise taxes on wealthy individuals to rectify the issue, while only 12 percent believed that taxes should be increased on “people like them”.[1]

In two previous posts[2],[3] we addressed claims related to inequality, social mobility, and economic growth where we ultimately concluded that shares of income have not changed all that much across income percentiles over the last half century and that to the extent that those in the lower economic classes have stagnated in mobility, this could reasonably be due to excessive governmental legislation, which has made it arguably much harder for individuals to leave places with lower levels of opportunity for places with greater job prospects. However, still, one could reasonably ask whether there is some truth to this notion that the U.S. in particular stands alone relative to its democratic comrades with respect to its approach toward market economics? Does the U.S. spend relatively less on its poor to the benefit of the wealthy?

Placing the U.S. Tax Regime in Context

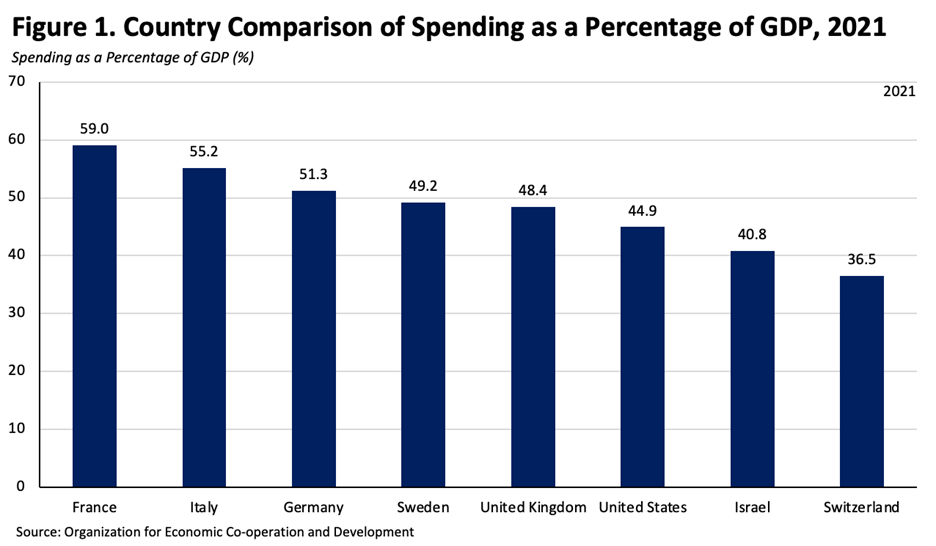

When comparing the U.S. government’s spending as a percentage of GDP, the U.S. is actually much closer to European countries than many would guess. In 2021 for example, government spending in the US at the federal, state, and local levels combined reached almost 45 percent of the country’s total GDP. The United Kingdom was just slightly above the U.S. at 48.4 percent, while Israel and Switzerland actually had lower percentages than the U.S. coming in at 40.8 and 36.5 percent, respectively (see Figure 1).

Historically speaking, while the U.S. initially had much lower levels of spending relative to the countries of comparison in Figure 1 through the 19th century and into the early 20th century, this began to change dramatically around 1920. From then on, the U.S.’s spending followed a remarkably similar growth path to those of European countries (see Figure 2).

Who is financing this increased spending? If it is people lower in the income distribution themselves, then one could say the system still benefits the wealthy.

Let’s start with the federal income tax. When looking at the percentage of income taxes paid by income percentile, this is clearly not the case. In 2020 for example, the top 1 percent of income earners accounted for 42.3 percent of all income taxes collected, while the bottom 50 percent of taxpayers accounted for just 2.3 percent (See Figure 3).[4]

Still, this could reasonably mean that while the top 1 percent pay more in the tax share, they still may be on the hook for less money as a percentage of their incomes. In other words, they could theoretically pay a lower average tax rate relative to the bottom 50 percent while also paying a greater share of the revenues. But, again, this also proves false. When looking a 2018 breakdown of average tax rates across income groups, the Joint Committee on Taxation found that while the bottom 50 percent of taxpayers had an average tax rate of 6.3 percent, the top 0.01 percent of taxpayers had an average tax rate of 32.9 percent (See Figure 4).[5]

The U.S. has quietly had one of the most progressive income tax regimes in the world for quite some time. In fact, a 2008 report from the OECD – the last time the OECD authored a report on the topic – found that the U.S. had the most progressive income tax regime in the world (See Figure 5).[6]

This all might seem slightly surprising since much of the prevailing narrative around the U.S. tax system is that it is highly regressive. For example, Emmanuel Saez and Gabriel Zucman claimed in their recent book The Triumph of Injustice that average tax rates are generally flat across the income distribution with only the very top income earners benefiting from lower average tax rates.[7]

However, as is always the case, the devil is in the details. Garrett Watson of the Tax Foundation points out that Saez and Zucman leave out the refundable portion of tax credits and cash transfers from their average tax rate calculation, which significantly reduces the tax burden for those at the lower end of the income distribution.[8]

In a report authored by Vermeer et al. (2023) from the Tax Foundation, the authors find that when accounting for everything including transfer income, the bottom quintile received an effective tax-and-transfer benefit of $1.27 for every dollar of income earned while the highest quintile received an effective reduction of $0.31 for every dollar of income earned. To illustrate how this works, the authors provide a useful example. Suppose a household in the bottom quintile of the income distribution earned $22,491 in pre-tax and transfer income. With our current tax system, this individual ultimately earns a total of $54,900 in post-tax and transfer income since this household receives an estimated $32,409 in net government transfers.[9]

Where Does the Money Go?

In 2022, the state and local governments and the federal government spent almost 10.5 trillion dollars.[10] When breaking down how that money was spent, the majority of spending went to some sort of transfer or entitlement program. Health care and social protection expenditures alone accounted for almost half of all expenditures, coming in at 49.9 percent. This does not include other forms transfer programs (e.g., Temporary Assistance for Needy Families etc.) that push this percentage well into the majority of all expenditures (See Figure 6).

So, with a current tax system that primarily taxes the wealthy, an ever-growing debt total, and a population that has no appetite for seeing its own taxes increased, are people satisfied with the federal government’s approach toward spending and the programs it finances?

The answer to this question is largely no. For example, despite receiving almost half of all government expenditures, the country is equally as satisfied as it is dissatisfied with Social Security and Medicare systems (45-45 percent).[11] Yet even with the current large levels of spending, these programs are expected to be underfunded relatively soon with Social Security expected to run short of cash in 2033[12] and Medicare in 2031.[13] And since the current political dynamics surrounding these two programs make reforms unlikely in the short-term since no one wants to incur the costs associated with higher taxes or reduced benefits[14], it is more likely that austerity measures will be imposed out of necessity in the coming decades.

A potential criticism to the poll mentioned in the prior paragraph is that the “dissatisfaction” indicated by respondents is not due to the program’s inefficiency but rather because the government does not spend more on that program to provide more expansive benefits. Suppose this is true. How will those individuals who desire greater spending feel upon finding out that due to the current funding levels of these programs, they are in actuality receiving a bargain for their current level of care? In fact, it will more than likely require additional funding through higher taxes on them[15] to simply keep the system running as currently designed. Thus, no matter how you view it, it is hard to imagine that satisfaction with these programs will increase after these new costs are imposed on taxpayers whether it is because individuals are frustrated with reduced levels of care or because of the realization that increased funding levels will merely retain the status quo.

Beyond the costs and perceptions of these programs is the fact that it is unclear that these programs can yield better outcomes for patients. In a now famous 2013 paper published in the New England Journal of Medicine authors Baicker et al. (2013) studied the 2008 expansion of Medicaid coverage for low-income adults in Oregon. Observing healthcare outcome differences between those selected and those not selected, the authors found that “Medicaid coverage generated no significant improvements in measured physical health outcomes”.[16]

Education funding also comprises a fairly large percentage of the government’s expenditures at 13 percent. Yet despite receiving such a large share, a majority of Americans (55 percent) are either “somewhat dissatisfied” or “completely dissatisfied” with the quality of education their children are receiving.[17] In recent years, parents’ attitudes toward their children’s schools has worsened significantly. Due in large part to the incompetent policies imposed on schools during the COVID-19 pandemic, the overall rate of parents choosing to homeschool their kids has grown dramatically from 5.4 percent to 11.1 percent, according to the U.S. Census Bureau.[18] The most recent data on nationwide test scores show that the these same policies erased two decades worth of gains in math and reading scores.[19] Many of these negative impacts were heavily concentrated on poorer students[20], as many wealthier parents were able to simply move their kids into private schools or provide them with individual tutors for instruction.[21]

Finally, a substantial portion of government expenditures are spent on public welfare programs. On the federal level, approximately 20 percent of federal expenditures are dedicated to over 80 public welfare programs, translating to about $9,000 spent per American household.[22] State and local governments also dedicate a substantial portion of their expenditures on these programs, spending over $2,500 per household on public welfare.[23] While well-intentioned, these programs often can impose long-term costs on those supposedly benefiting. For example, as Yale Law School’s David Schleicher finds that the difficulty of carrying public benefits across state lines has likely harmed inter-state mobility, which can have long-term economic consequences for individuals not able to take advantage of the benefits of higher opportunity areas.[24]

Conclusion

We do not contend that all major areas receiving government funding should be abolished. Instead, we are pointing out that many of the narratives surrounding the U.S. tax system are either grossly exaggerated or completely wrong. In particular, we are taking aim at the idea that the tax system overwhelmingly benefits the wealthy at the expense of the poor.

As it turns out, the truth is that the U.S. actually has an extraordinarily progressive tax regime that taxes the wealthy at much higher effective rates relative to taxpayers at the lower end of the income distribution. Large portions of government revenues are already directed at redistributing money from the rich to the poor in the form of public welfare and other income assistance programs.

Yet despite these efforts, many people are dissatisfied with what the government is providing. For some of these major programs, levels of satisfaction will almost certainly get worse once Americans discover that their taxes will necessarily need to be increased to keep the current levels of benefits. Further, beyond Americans’ perceptions of these programs, it is unclear whether these programs are even yielding any better outcomes for those receiving them (e.g., Medicaid) or setting up citizens for long-run success (e.g., state-specific welfare programs).

There are only two possible paths to improvement. Either government spending must get much more efficient, or more services have to become privatized to improve outcomes and reduce the citizens’ dependence on government programs. It would be preferable if we chose these paths ourselves rather than wait until our unsustainable debt burden forces sudden and drastic action.

[1] https://www.pewresearch.org/social-trends/2020/01/09/most-americans-say-there-is-too-much-economic-inequality-in-the-u-s-but-fewer-than-half-call-it-a-top-priority/

[4] https://taxfoundation.org/data/all/federal/summary-latest-federal-income-tax-data-2023-update/#:~:text=High%2DIncome%20Taxpayers%20Paid%20the%20Majority%20of%20Federal%20Income%20Taxes,of%20all%20federal%20income%20taxes.

[5] https://taxfoundation.org/data/all/federal/us-tax-system-progressive/

[6] https://read.oecd-ilibrary.org/social-issues-migration-health/growing-unequal_9789264044197-en#page14

[7] Emmanuel Saez and Gabriel Zucman. “Income and Taxes in America.” The Triumph of Injustice: How the Rich Dodge Taxes and How to Make Them Pay, W. W. Norton & Company, New York, NY, 2020, p. 15.

[8] https://taxfoundation.org/blog/emmanuel-saez-gabriel-zucman-triumph-of-injustice/

[9] https://files.taxfoundation.org/20230330132050/Americas-Progressive-Tax-and-Transfer-System-Federal-State-and-Local-Tax-and-Transfer-Distributions-2.pdf?_gl=1*1eaignz*_ga*NjQzOTg2MzY4LjE2OTE1NTA3NjE.*_ga_FP7KWDV08V*MTY5MTYwNDEzOS4yLjAuMTY5MTYwNDEzOS42MC4wLjA., pg. 2.

[10] https://www.cato.org/blog/where-did-tax-dollars-go-federal-budget-breakdown#:~:text=The%20federal%20government%20spent%20%246.3,be%20paid%20for%20by%20taxes.

[11] https://news.gallup.com/poll/470894/americans-fairly-satisfied-social-security-system.aspx

[12] https://www.npr.org/2023/03/31/1167378958/social-security-medicare-entitlement-programs-budget

[13] https://www.healthcaredive.com/news/medicare-trustees-report-solvency-2031/646627/#:~:text=Medicare's%20hospital%20trust%20fund%20is%20now%20expected%20to%20go%20broke,home%20stays%20and%20home%20healthcare.

[14] https://www.aei.org/op-eds/why-congress-will-never-reform-social-security/

[15] While many may say in response that taxes can just be increased on the “rich” to pay for these programs, the assumption about how much revenue this would actually provide the government is often incorrect. Using IRS data for example, assuming all individuals over $1 million per year allow the government to completely confiscate all their income in a given year, this would only yield an addition $1.3 trillion in revenues. The average yearly additional cost for a “Medicare for All” type scheme according to Charles Blahous of the American Enterprise Institute would cost approximately $3.26 to $3.88 trillion per year. European countries that have more expansive healthcare systems often rely on VAT taxes which are much less progressive tax systems to fund their programs.

[16] https://www.nejm.org/doi/full/10.1056/nejmsa1212321

[17] https://news.gallup.com/poll/1612/education.aspx#:~:text=Line%20graph.,who%20say%20they%20are%20dissatisfied.

[18] https://www.newsnationnow.com/us-news/education/more-parents-than-ever-turning-to-homeschooling/

[19] https://www.nytimes.com/2022/09/01/us/national-test-scores-math-reading-pandemic.html

[20] https://www.brookings.edu/articles/the-pandemic-has-had-devastating-impacts-on-learning-what-will-it-take-to-help-students-catch-up/#:~:text=Even%20more%20concerning%2C%20test%2Dscore,the%202020%2D21%20school%20year.

[21] https://www.wsj.com/articles/wealthy-families-stick-with-full-time-tutors-hired-early-in-pandemic-11662543002

[22] https://budget.house.gov/press-release/7582/#:~:text=In%20fiscal%20year%202022%2C%20the,%249%2C000%20spent%20per%20American%20household.

[23] https://www.taxpolicycenter.org/statistics/state-and-local-general-expenditures-capita

[24] https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=2896309